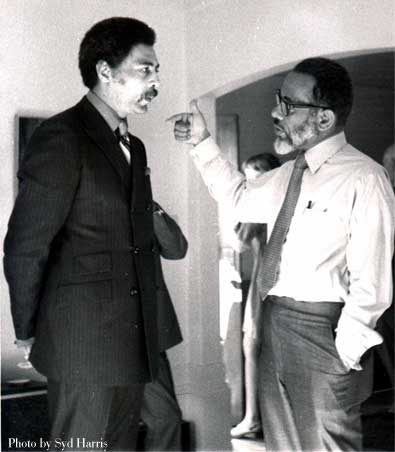

In honor of Juneteenth – a day to celebrate African American resilience and remember the harms perpetrated by our nation – we continue our work highlighting the legacy of Alonzo King’s family. Today, we commemorate one of his uncles, C.B. King, a courageous lawyer who defended countless civil rights activists, including Martin Luther King, Jr.

C.B King was born and raised in Albany, Georgia, and educated through the segregated school system. His awareness that the law did not protect people who looked like him became apparent at 10 years old. Playing with other kids near his house, a policeman drove up, jumped out of his car, and pointed around a gun. “I hid under a building but some of the kids were arrested for ‘vagrancy’ or ‘loitering,’” King recalled in an interview with Ellen Lake for The Harvard Crimson. “Right then, I felt that there was something wrong with the way the law operated in the Negro community.”

Education seemed like one way to right wrongs. Following in the footsteps of his parents, Margaret Slater (student of Nashville’s Fisk University) and Clennon W. “Daddy” King (graduate of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute), King set his sights on higher education. After graduating in 1949 from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, King applied and was denied access to Georgia’s white-only law schools. Refusing to concede, he enrolled at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

Upon graduation in 1952, King was wed to Carol Roumaine and ready to take a stand in his hometown. He opened a law practice in Albany in the mid-1950s, being the first Black man in in that city to represent his own clients and the only attorney south of Atlanta to litigate civil rights cases. King defended the victims of an oppressive and persisting system of Jim Crow laws, laws which shadowed him as well.

When King asked for water in court, he was brought a bucket and a ladle. When he requested that the judge halt proceedings, he was refused. And when he sat in the lawyer’s box, the first Black man to ever do so, a sheriff told him to get out. “King, we ain’t had no trouble before you come here, and we don’t want none now,” King recalls the sheriff saying. “You go back and sit with the other niggers. Do you hear me, boy?”

Yet even in a sea of all-white jurors, court officials, and judges, King refused to stand down. His courage, courtroom grace, and legal knowledge were fierce in the face of opposition; his mastery of language and near photographic memory formidable.

King’s skill was instrumental in the Albany Movement, the first mass movement in the modern civil rights era aiming to desegregate a whole city. He led the legal charge in the 1960s, defending protestors and negotiating them out of jail.

“I like to practice law… because I’m in the peculiar position of being able to talk to twelve people who have to listen to what I say. White men usually think the Negro is invisible, they don’t look at him. But in court I am the action–they have to look at me. If nothing more, just the trauma of my blackness confronting them in this setting is educative.” — C.B. King

In 1962, while asking permission to visit a white civil rights protester who had been badly beaten in prison, King was viciously caned by a county sheriff, the same one who had earlier told him to vacate the lawyer’s box. A photograph of the bleeding C.B. King was printed in The New York Times and viewed worldwide. Shaken but unrelenting, King continued to fight in the courts, defending noteworthy clients such Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, Andrew Young, and William G. Anderson, leader of the Albany Movement.

In 1964, King campaigned for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was the first Black candidate in Georgia to run for Congress since the Reconstruction era. Five years later, nominated by the state’s Black leadership, he became Georgia’s first African American candidate for governor. His races, while unsuccessful, would motivate others of color to run for office.

King shared his experience with the next generation, mentoring a number of law interns and activists, many of whom went on to be respected judges, members of Congress, and environmental and civil rights advocates. In addition, King’s efforts to integrate the jury system led to the 1968 Jury Selection and Service Act.

Weeks before he passed away from prostate cancer in 1988, the Georgia state legislature formally recognized his contributions. At the state capitol, Governor Joe Frank Harris presented him with the first Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award. To further honor his legacy in 2002, the United States government named its new federal courthouse in Albany in his honor.

C.B. King was a husband, father of five, and a persistent advocate for those whose justice system did not serve them. We honor King for the risk he undertook every day to correct the wrongs of racism, and welcome in a new generation of Black leaders.

For further reading on C.B. King, visit our sources:

Albany Movement, New Georgia Encyclopedia

C.B. King (1923-1988), CLT Roots

C. B. King (1923-1988), New Georgia Encyclopedia

C.B. King, The Harvard Crimson

C.B. King Obituary, The New York Times

Photography sourced from:

Albany historian working to stop historic building demolition, WALB

C. B. King (1923-1988), New Georgia Encyclopedia

Written by Erin McKay