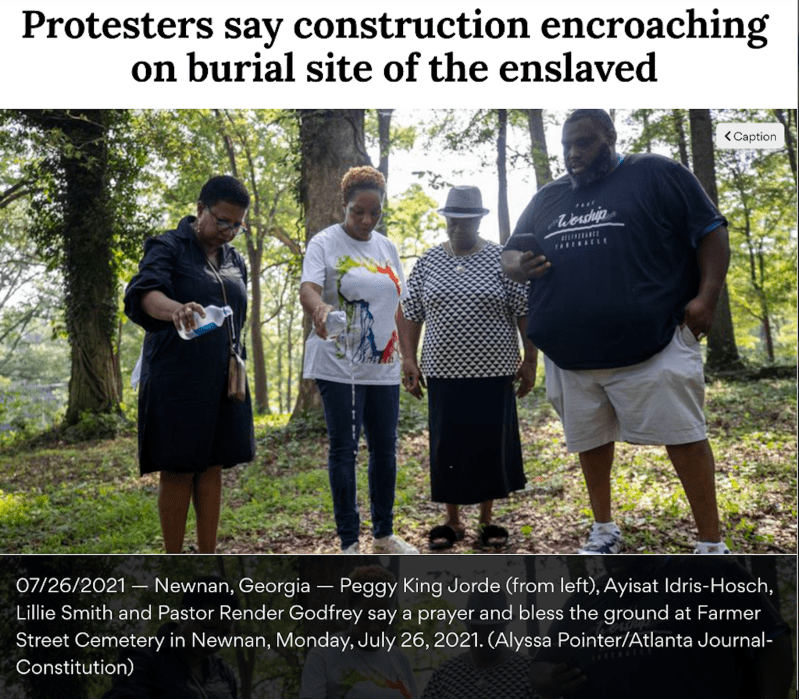

In honor of Juneteenth, we interviewed Alonzo King’s cousin, Peggy King Jorde, a Cultural Projects Consultant combining more than 30 years of experience in planning, design, public art, and historic preservation. Peggy served under three New York City mayors and was a pivotal figure in the 1990 fight to protect a 17th-century African burial ground in the city. Her work also extends internationally, where she consulted government and community stakeholders on a development project in the British Overseas Territory of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, which is believed to be “the largest burial ground of enslaved Africans direct from the Middle Passage.” To amplify the project, Peggy produced and participated in the British documentary entitled A Story of Bones, which premiered in June 2022 at the Tribeca Film Festival. Read on to learn more about this remarkable woman who lives a life of service.

Interview by Erin McKay

How did your parents inspire you as a child? How do they inspire you today?

My parents and family are my North Star. My mother, a native of Cleveland, Ohio, had just started her career teaching at a Jewish Daycare for children when she met my father. In fact, as a child, I remember how she could recite the seder prayers in Hebrew when prompted. Dad was in Law School at Case Western Reserve, and he had plans to return to Georgia to practice law. It was how he planned to overturn the oppressive circumstances of Black people in the South and across the country. They were married and lived in Cleveland for a year or more until he passed the Georgia Bar. Despite protestations by Mom’s relatives fearing a move to the hostile South, Mom and Dad committed their lives to each other and to an uncertain future in Southwest Georgia.

My parents’ lives were full—a family of four boys and me, the only girl. A life of service was at the heart of their vocations; in fact, “service” was at the heart of the community. Racial terrorism dictated that the livelihood of any Black community relied upon collaboration, spiritual centering, and a solid sense of community to stay safe and thrive. I will never lose sight of the fact that I was born into an American apartheid in the basement of a segregated hospital in Albany, Georgia.

Mom eventually left teaching and founded the Head Start Program, educating and supporting socio-economically marginalized families and their children. Her commitment to single mothers and their children was phenomenal. Not only did she inspire the children, but she lifted up their mothers and their extended families in ways that helped them reach unforeseen successes in their lives. Many became breadwinners and community leaders in their own right.

Dad’s law practice positioned him as the sole Black attorney in Southwest Georgia at the dawn of the Albany Civil Rights Movement, during which he was the attorney to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Owing to his superb legal insight, some of us landed squarely in the sights of a lawsuit to enforce the desegregation of public schools. Desegregation was a strategy that would ensure equal access to the wealth of public resources financed by all citizens but afforded only to white citizens. By September 1964, I was one of the first to test that strategy by desegregating my first-grade class at an all-white public elementary school. I had become a part of the movement that ignited a cultural and social shift. It is an experience that will forever inform my work in heritage protection.

You have a background in costume design and architecture. How does art influence your heritage protection work?

Acts of remembrance are a profound part of my personal journey, and no act of remembrance has marked my life more than designing and handcrafting my father’s coffin with my brother. Design and storytelling are a part of my professional toolkit. My collaborations with descendant communities, architects, design professionals, artists, and filmmakers permit me to explore, guide, and interpret a variety of options for meaningful expressions of remembrance.

I have also collaborated using filmmaking and storytelling as tools to further amplify the importance of preserving and sharing these narratives. I am the Consulting Producer and a protagonist for the documentary A Story of Bones. Since its release at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival, we have used this film as our call to action in a global impact campaign to bring about awareness and amplify the movement around African burial ground protection.

Can you tell us about the bond that your father, C.B. King, shared with Alonzo’s father, Slater King?

My father’s family were well-established entrepreneurs, educators, and leaders in the Albany community. His parents met during their years in college, one at Fisk and the other at Tuskegee, and raised a family of seven sons. Uncle Slater King, Alonzo’s father, was Dad‘s closest of brothers, a partner in business and an ally in the movement for social change. Uncle Slater’s untimely passing was a devastating loss for the family, but particularly for my father. The bond between Uncle Slater and Dad was profound and irreplaceable. They had a shared vision for change and an unwavering commitment to the community.

Community activation is critical to your work in cultural preservation. What strategies have you found work best to get the community on board and invested?

African burial ground protection and sacred site preservation require descendant communities to reclaim spaces often in the hands of others who may refuse to recognize that it was never theirs to own and who do not understand that there remains an outstanding debt owed for reparative justice. Communicating these concepts to others is crucial to garnering an understanding and fostering support for sacred site protection. It requires activists to challenge hegemonic practices and ideas that have perpetuated the marginalization of these spaces and communities.

You were the executive director for the New York African Burial Ground Federal Steering Committee. What was your approach to honoring this historic site?

Empowering the voices that have been historically marginalized and providing opportunities for meaningful expression is crucial to my work. By listening to and learning from the perspectives of those most impacted by these histories, we can begin to truly honor and preserve the rich narratives and experiences of descendant communities.

The creation of the African Burial Ground Monument and Interpretive Center is a testament to the activism, bravery, and dedication of many who have worked tirelessly to reclaim the sacred site and its history. Our efforts not only acknowledge the painful legacy of the transatlantic slave trade but also set a global example for fostering cultural integrity and truth-telling in memorialization initiatives.

Connecting narratives like the New York African Burial Ground across borders and cultures is also essential for recognizing the interconnectedness of the histories and legacies of the transatlantic slave trade. By acknowledging and honoring these histories collaboratively and inclusively, we can work towards a more comprehensive and truthful understanding of our past. The impact is far too significant to ignore, and it matters how we choose to remember.

How does your work bring you joy?

The stories we tell ourselves and the stories we tell each other have meaning. They are powerful and can profoundly impact who we are and how we engage with one another as individuals, communities, and a nation.

The deliberate omission, silencing, and misrepresentation of historical narratives, sacred places, and cultural heritage disproportionately affect Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities.

When there is an opportunity for me to engage in meaningful collaborations and effect social change using film, art, design, remembrance, and storytelling, it brings me profound joy.

A question from Alonzo: As exemplified by your family, you’ve lived a life of service to others. What has that taught you?

I’ve learned that people give meaning to culture, history, and places. That no matter the lineage, we’ve been a part of each other’s lives since the beginning of time. My years of practice in cultural heritage have taught me the truth about who we are and where we’ve come from.

That in order for any of us to be here right now,

somebody before us had to survive something;

somebody before us had to overcome something;

somebody before us had to endure something;

but the most precious of these is that somebody before us loved someone.

This is the legacy I carry with me always.

To learn more about Peggy King Jorde’s work, visit: kingjordeculturals.com.

Banner Photography: Annina van Neel (L) and Peggy King Jorde (R) in a cotton field, in Albany, Georgia. Road trip through the American South. Documentary filming for A Story of Bones in 2018. Photograph by PT Films.

Love these conversations? In addition to these interviews, LINES Ballet’s performances and education programs reach more than 30,000 people every year. But we need your help. We rely on donors’ generosity to bring these inspirational programs to our community. Donate today!