In honor of Black History Month, we celebrate the immense contributions that Alonzo King’s father, Slater King, and uncle, C.B. King, made to the civil rights movement and the betterment of life for Black Americans.

Slater ran a successful real estate business in Albany, Georgia, that helped Black residents gain economic independence through home ownership. C.B.—an attorney—ran the only Black law firm south of Atlanta that took civil rights cases.

In 1961, arrests of student sit-in activists spurred the King family, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and other local organizations to form the Albany Movement, the first mass movement in the modern civil rights era aiming to desegregate an entire community.

Slater King explained how the movement served the community and where he wanted to see it bolstered in The Bloody Battleground of Albany, originally published as Freedomways in 1964:

For two years the Movement has been the place where the Negroes have come for inspiration, to learn Negro history, and to further the strong feeling of identity, to know that they are not alone, to learn how politics work, and how they have been taken advantage of. They have heard speakers with opinions ranging from Dr. Lonnie X. Cross, representative of the Black Muslims to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., representing the integrationist…

We have aroused emotions of the people and whetted their desire for freedom but we have not done the thorough organizational work which I think is essential to the success of any movement. You have to have emotion, but you also have to have discipline, well-thought-out plans that our best minds must help draft, and army-like discipline…to really be effective in our Movements across the country, we must unite these three ingredients: Protest, Political Mobilization, and Economic Unity.

—Slater King

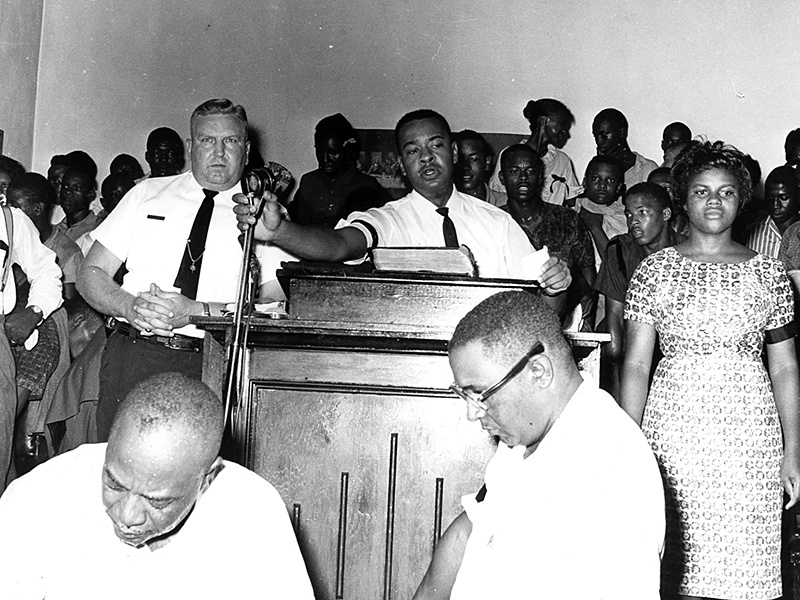

Slater King was elected the coalition’s vice president, and later president, and C.B. became its attorney, negotiating protestors out of jail, including Martin Luther King Jr., who shared a cell with Slater numerous times in support of Albany’s desegregation efforts.

C.B. recalls the pulsing threat and dehumanizing opposition he faced in the courtroom in The People’s Lawyers by Marlise James.

I proceeded to wittingly exercise what had heretofore been the exclusive right and privilege of white lawyers, to sit and observe the law at work from close up…The second day I again sat there and upon this occasion the sheriff came over and told me, ‘Go sit with them other n****rs.’ I was numbed by my embarrassment…and snickering of lawyers and other court officers…This encounter abrasively reasserted an identity I was in the process of forgetting. I explained to the sheriff that, as an officer of the court, I had a right to use the jury box as did the others.

At this time it was close to the time of the trial of my client, the boy who had been charged with resisting arrest whom I was yet to defend. I left my seat attempting to convince myself that in so leaving I was not yielding to the sheriff’s threats but rather recognizing my duty and concern not to prejudice the case against my client. I walked out into the rotunda with the sheriff and protested this patent differential treatment. The sheriff said, “We ain’t had no trouble before you come here, we ain’t going to have none now.” I walked to the outside of the courthouse in an effort to overcome a sort of drowning that is common to humans who have been stripped of a sense of self. Yes, I cried a bit as well…

So the next day I returned to the courtroom and to the jury box from whence I had previously gone…Again the sheriff came and said, “G*****n it n****r, I thought I told you to get back there with them other n****rs. Do you want me to hurt you?” I looked into the face of the sheriff as dispassionately and as calmly as I could under the circumstances and said, “Sheriff, that’s what you will have to do, I’m staying here.” He then told me that he’d give me five minutes to move…The interim between the sheriff’s last warning and his return to the courtroom represented moments of intractable nightmarish anxiety for me. I expected at any moment that he would return and there brutalize me in this forum of white justice. When he did return, instead of coming to where I was, he went to the judge’s bench and in that instance I was sure that I had prevailed.

—C.B. King

In 1963, Slater ran for the mayor’s office in Albany. While he did not win, Slater explains the accomplishments of the campaign in The Bloody Battleground of Albany:

…the candidacy…consolidated the Negro vote and formed one bloc unit where Negroes voted 90 per cent together on all of the candidates…The racists have a monopoly of the news, but through paid television appearances, we were able to tell the other half of the story. I stated the Negro demands unequivocally which opened many eyes and gained some white supporters. We created a new image for Negro boys and girls, a quickening interest in the political, and a desire to take part in the political sphere…One of the items that we spoke against in the campaign was the lack of a Negro truant officer in Albany. Now, a trained truant officer, a college graduate, has been hired.

—Slater King

A year later, C.B. ran for the U.S. House of Representatives (as the first Black man in Georgia to run since the Reconstruction era). His campaign inspired 2,500 new voters to register. But as more Black voters rallied to the polls, retaliations ensued.

Tenant farmers and sharecroppers in Albany were systematically forced off their land when they tried to register to vote. To fight back, Slater King, Charles and Shirley Sherrod (SNCC organizers), and other activists came together to found New Communities Inc., a non-profit aimed at acquiring collectively owned and farmed land. Slater was elected president.

New Communities, Inc. is still alive today, and after a decade of battling the USDA for discriminatory practices, it was awarded $12 million in 2009, which it used to purchase the Cypress Pond Plantation in 2011.

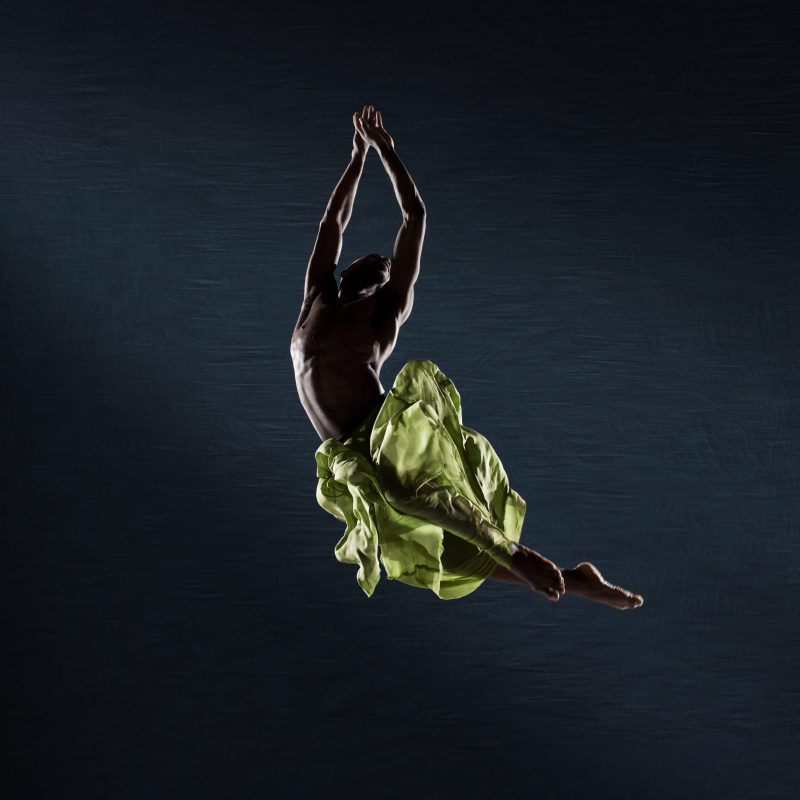

Slater King’s and C.B. King’s tenacity, creativity, quick wit, and commitment to the prospering and protection of Black Americans deeply impacted Alonzo and still runs through the veins of LINES Ballet today.

Written by Erin McKay

Photography (credited from top to bottom):

Slater King | Courtesy of New Georgia Encyclopedia; C. B. King | Courtesy of Carol King; Albany police chief Laurie Pritchett with Slater King in Shiloh Baptist Church | Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography; (Left to right) Attorney T. M. Jackson, chief counsel Donald Hollowell, Dr. William G. Anderson, and attorney C.B. King | Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography; Slater King and Irene Asbury Wright lead a group of protestors in Albany | Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography; Thomas Chatmon, Marion King, and an unidentified woman register to vote. They are accompanied by young Jonathon King and Slater King (far right) | Courtesy of Cochran Studios/A. E. Jenkins Photography

For further reading, visit our sources:

Formwalt, Lee. “Albany Movement.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Jul 15, 2020. georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/albany-movement

“King Family.” SNCC Digital Gateway. snccdigital.org/people/king-family

Lawson, Mary. “C. B. King.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Mar 28, 2021. georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/c-b-king-1923-1988

Lawson, Mary. “Slater King.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Aug 27, 2020. georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/slater-king-1927-1969

“New Communities formed in Southwest Georgia.” SNCC Digital Gateway. snccdigital.org/events/new-communities-formed-in-southwest-georgia

“Seeding the First CLTs: New Communities Inc.” Roots & Branches. cltroots.org/the-guide/early-hybrids-breeding-and-seeding-the-clt-model/georgia-seedbed

King, Slater. The Bloody Battleground of Albany. Originally published Freedomways, 1st Quarter, 1964. Civil Rights Movement Archive. crmvet.org/info/sking.htm

The Center for Guerilla Law. guerrillalaw.com/CBKing.html

“The Movement Never Ended.” SNCC Digital Gateway. snccdigital.org/our-voices/strong-people/part-4

LINES BALLET’S 2025 SPRING SEASON

Experience Alonzo King’s first-ever collaboration with American jazz trumpeter/composer Ambrose Akinmusire. According to The New York Times, “even in its simplicity, Akinmusire’s trumpet can feel almost dangerously tender.” King’s timeless ballet Scheherazade will also return to the stage in full after over a decade. Spring Season performances run from May 10–18 at YBCA’s Blue Shield of California Theater.

Photography: Alonzo King LINES Ballet | Dancer: Keelan Whitmore | © RJ Muna